Introduction

The 2002 sequencing of the human genome revolutionized our understanding of human disease, giving us heretofore unknown information about the genetic drivers of disease and, by extension, direction on how to address it. Though we have started to harness that revolution in drug discovery and development over the past 16 years, there is still a massive amount of white space that remains to be elucidated and addressed. This post will provide a snapshot of where we stand in drugging the druggable universe.

The Druggable Protein Universe

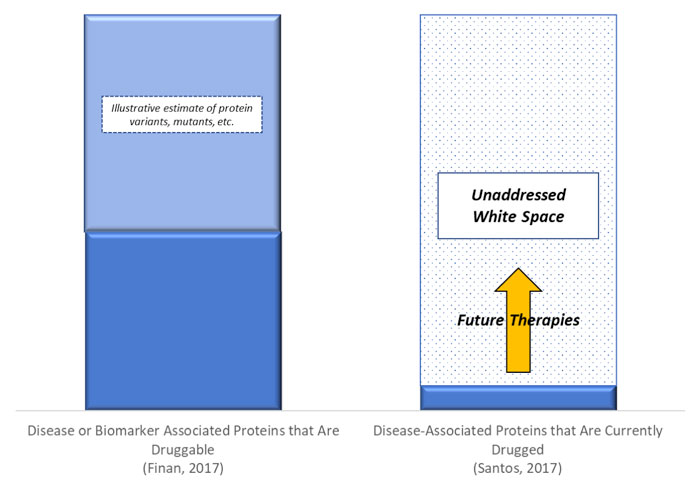

There are an estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome (Salzberg, 2018). A 2017 review estimated that 4,479 of these genes encode disease- or biomarker-associated proteins that are “drugged or druggable” (Finan, 2017). A separate 2017 meticulous review concluded that all Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) drugs approved over the past 100+ years (approximately 1,200) have targeted only 667 total molecular targets (549 for small molecule drugs, 146 for biologics) (Santos, 2017).

These analyses rely on separate methodologies and definitions, requiring caution when comparing them directly. Notably, the Finan review likely dramatically underestimates the number of protein targets in the universe due to protein variations such as mutations, some of which may cause a protein have dozens, scores, or even hundreds of different conformations.

While the exact magnitude of difference between druggable targets and currently drugged targets may be uncertain, we believe the direction is not, and conclude that substantial white space exists between druggable disease-implicated targets and currently available therapies that will be addressed with future therapeutic approaches. (Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1: Druggable Protein Universe Compared to Targets of Existing Drugs, 2017

Source: Finan, 2017 and Santos, 2017

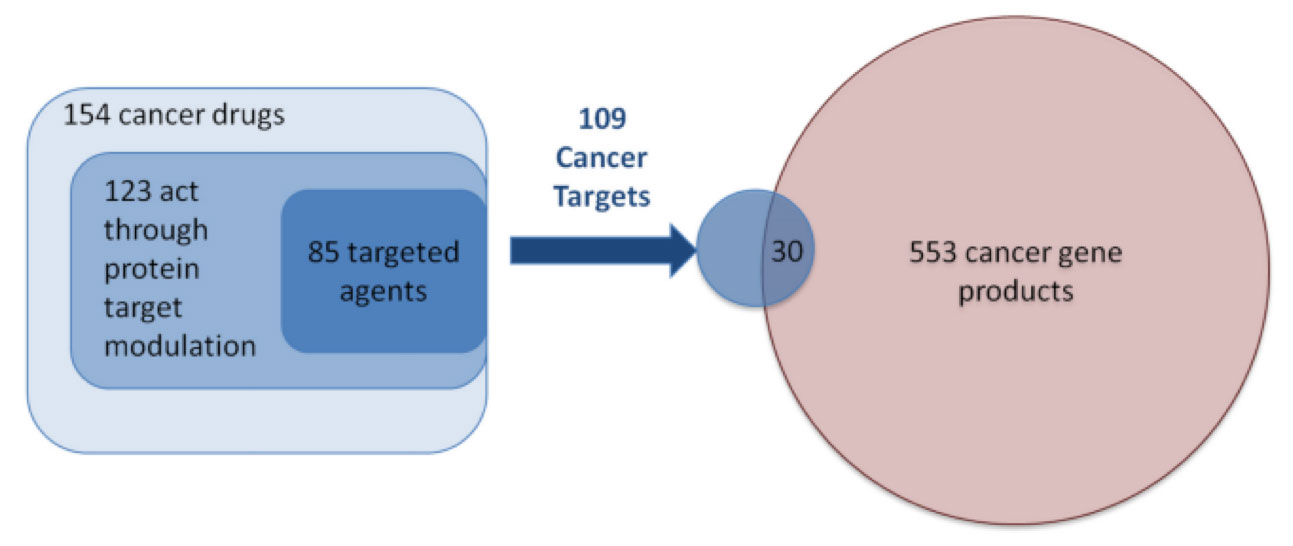

Case Study: Oncology

A 2017 study of oncology therapies further illustrates the point. A consensus is reportedly converging that there are approximately 600 cancer driver proteins (Workman, 2013). As of 2017, there were 154 cancer drugs approved by the FDA targeting 109 protein targets – of which only 30 overlapped with the consensus 553 cancer driver proteins (Santos, 2017). Per this analysis, only approximately 5% of all driver proteins in oncology are currently targeted, leaving substantial white space for novel approaches. (Exhibit 2)

Exhibit 2: Overlap of Cancer Drug Targets with Cancer Drivers

Source: Santos, 2017

What’s more, this estimate does not include other non-driver protein targets implicated in cancer, such as synthetic lethal targets, loss of function drivers, immune-based targets, or non-protein targets such as ribonucleic acid (“RNA”).

Conclusion

The revolution in our understanding of disease, enabled by the Human Genome Project, has unleashed an unprecedented era of drug development. We believe that this understanding, coupled with the massive white space in unaddressed disease-associated protein targets, will make investing in therapeutics companies a fertile ground for the decades to come.

Limitations

Each paper cited relies on its own distinctive methodology and, at times, requires the author’s discretion. This makes cross-study comparison challenging.

Sources:

•Finan, “The druggable genome and support for target identification and validation in drug development,” Science Translational Medicine, 2017.

•Salzberg, “Open questions: How many genes do we have?” BMC Biol, 2018.

•Santos, “A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets,” Nat Rev Drug Discovery, January 2017.

•Workman, “Drugging cancer genomes,” Nat Rev Drug Discovery, 2013.

This information is not intended to provide investment advice. Nothing herein should be construed as a solicitation, recommendation or an offer to buy, sell or hold any securities, market sectors, other investments or to adopt any investment strategy or strategies. You should assess your own investment needs based on your individual financial circumstances and investment objectives. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast or research. The opinions expressed are those of Driehaus Capital Management LLC (“Driehaus”) as of May 2019 and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. The information has not been updated since May 2019 and may not reflect recent market activity. The information and opinions contained in this material are derived from proprietary and non-proprietary sources deemed by Driehaus to be reliable and are not necessarily all inclusive. Driehaus does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of this information. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this material is at the sole discretion of the reader.

Other Commentaries

Data Center

By Ben Olien, CFA

Driehaus Micro Cap Growth Strategy March 2024 Commentary with Attribution

By US Growth Equities Team